No one in their right mind would admit to seeing themselves as Cecil Vyse - Daniel Day-LewisBetween the ages of fifteen to seventeen, too deeply depressed to undergo any kind of emotional maturation, my half-hearted attempt at forging a personality relied on my being utterly contrarian.

As such, in conversation or indeed conversazione, my only contributions would be a noticeable lack of eye contact and a prominent, anxiety-induced speech impediment whenever I attempted to say something that I thought bore resemblance to a quip.

Once at dinner, I had finished stammering through my latest nonsense when a parent, I forget which one, looked at me quite levelly and said, “Lily, don’t be such a Cecil.”

Several years B.B. (Before Beaton), there was only one Cecil they could have been referring to; Cecil Vyse, Esq.

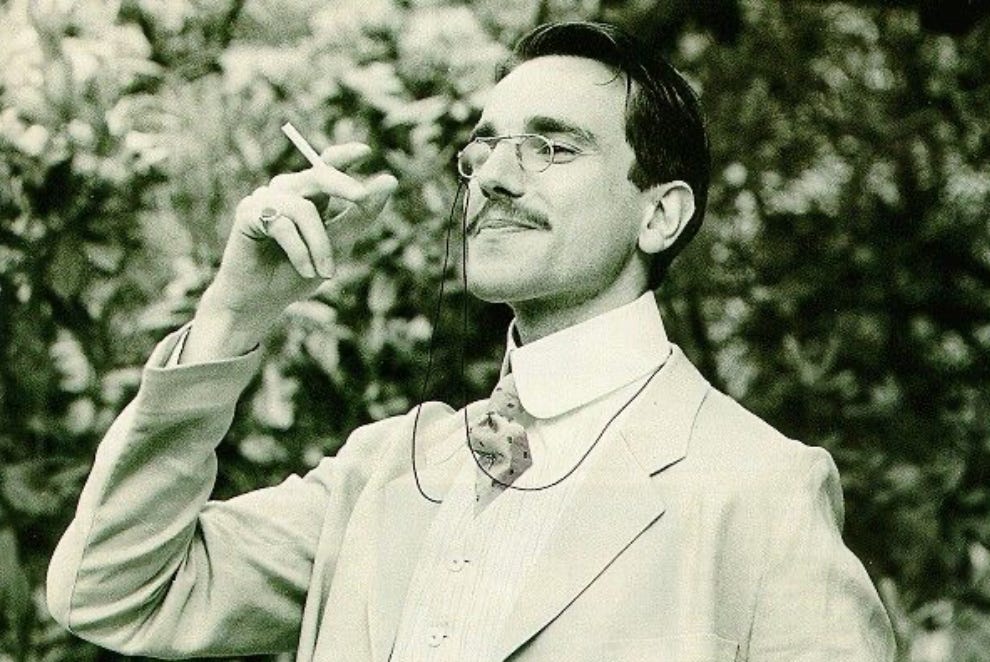

My heart bleeds for him. He’s the sort of person you imagine you might be in your worst nightmares. Desperately, desperately self-conscious and pompous…he can’t open his mouth without clearing a room - Daniel Day-Lewis on Cecil VyseCecil Vyse from E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View is the rebound of the novel’s protagonist, Lucy Honeychurch, who agrees to marry him after denying herself the possibility of a passionate affair with the roguish George Emerson.

An arrogant, ridiculous fop, Cecil is the architect of his own destruction when he unwittingly reunites Lucy with George. When Lucy is forced to choose between them, it is clear that she should not choose Cecil.

I watched Merchant Ivory’s adaptation of A Room with a View for years with a grim acceptance of one’s own isolation from the world. From the moment Cecil enters the Honeychurch’s Drawing Room with an elaborate cry of “I promessi sposi!” before immediately having to translate, he is an obvious outsider.

His time in the film is awkward blunder after blunder, poorly disguised by a veil of formality (which reminds me of a deeply sad girl who tried to give herself elocution lessons when she was sixteen), offering handshakes in lieu of embraces, leaving the room when people begin to sing, and crucially, refusing to play tennis. Lucy’s conclusion that she cannot marry him seems only inevitable.

When it is clear to Cecil that Lucy will not change her mind, he is all too quick to once again embrace his distance from the world. In his final moments, he puts on his boots and pince-nez, the finishing touches of a grand facade, before leaving quietly, alone and unacknowledged.

My sadness passed, and I reentered the world. With time, Cecil Vyse became emblematic of an old self that began to fade like a scar, to be regarded with a mix of both affection and pity. He is still the avatar on my long-defunct Tumblr, and I do recall once, when I was between jobs, changing my Instagram Bio to read, “I have no profession. My attitude - quite an indefensible one - is that as long as I am no trouble to anyone, I have the right to do as I like. It is, I dare say, an example of my decadence.”

But Cecil Vyse's resonations go far beyond me. He has achieved a second life on social media, where he is the subject of fake Twitter accounts and fan edits to Azaelia Banks’s 212. It should not be possible for this to happen to a character this much of a popinjay, but such is the talent of Day-Lewis's overly-affected performance, that Vyse is elevated from being a mere bore to gloriously camp1. He is, quite simply, baby boy.

Over ten years have passed since I was first decried as a Cecil, and whilst I am still slightly awkward about my own place in the world and perhaps a dash too self-important, it is something of a relief that the character from A Room with a View I likely bear the closest resemblance to now is the intrepid traveller and lady novelist Eleanor Lavish - even if I do insist on pronouncing her name in the Vyseian fashion, as Elena Laveesh. It is, I dare say, an example of my decadence.

Happy Birthday, Daniel! I love you and your choices, but if you change your mind about retiring, please know you have my full support. Big love to you, Bex and the kids xxx

Note: This was not an issue when Laurence Fox played him in the 2007 ITV Adaptation